I hardly spoke to him the last year. When the news came, I scrambled through my messages to find out the last time we had spoke, the last words he had said to me.

“I’m never going to stop hounding you to talk to me. I know sometimes I say the inappropriate but I’m a writer. I do hope that I haven’t distanced you with words. I love you so much it makes me cry. You have helped me get through personal anguish…and are my best friend.”

When I read it out loud the weekend he went further, my voice cracked, then shook; the tears rolled out of my mouth. The first time I read it, I squinted my eyes and slightly lifted the right corner of my top lip. The second time, this time, I choked, tripped over my panic, and fell.

He had emotions never repressed enough to go unnoticed and never small enough to be forgotten after they had passed. Whether filled with love and affection or bitter cruelty, they were all of the same grotesque nature that frightened me. I’d hold my breath until I could tiptoe away as delicately and quietly as possible, then go months without talking to him.

I didn’t respond that time. I didn’t talk to him for four months and would have kept not talking to him, but he died. He killed himself, slowly, drinking alcohol. He had chances. He’d been to the hospital a few times to be patched together, his booboos kissed and patted gently before getting all the information needed about his dying body in order to live. He’d always stop drinking and try his hand at living, but eventually he’d start trying to die again.

I spent the last year of his death hiding from what killed him: those God-Forsaking Emotions. I cried harder because I understood him too well; the lost music, the bruised writing, the un-beautiful drawing and always the disasters. Our lives were just so disastrous. I had had my own binges while visiting him, cocaine and peyote in the night, alcohol and marijuana throughout the day, cigarettes at all times. He only watched, only sipping alcohol throughout, but I wouldn’t (not couldn’t) notice that he only drank alcohol, all day, all night, even when I had come off a binge and was laying low.

The same thing killing him was killing me, too.

“Yeah I just spent two days doing research on bipolar and I have all the characteristics. You’re brilliant. Now I’m well again.”

Nothing I said before or after, but that’s how he’d write direct messages, like he’s in the middle of a very detailed conversation. Two months after researching what was killing him, he died. I knew it was killing him for years when I figured it out for myself–when I saw how alone I really was, looking at myself like I was watching a TV show–but only told him six months before. Remorse for not responding much, regret for not visiting more, but guilt for not telling him what mattered. He should have known, but I didn’t tell him. In the end, he helped me live and I had helped him die.

Shon always took the time to tell me that my life was worth living and needed to be lived as if he had it scheduled on his calendar. When words; music; life decided me repugnant, an email would appear in my inbox with a paragraph of nonsense, a noise clanging, mp3 file, or just three words. You are brilliant or You are beautiful or, and mostly, I love you.

“Sometimes you have to collect. Follow the sun and moon. Put your ear to the ground, taste the wind, play in the dirt, bathe in the ocean, scream loud onto the universe, Look at Saturn and watch the rings. Then write!”

Shon told me that he wrote everyday which is why he wrote a lot of crap. He didn’t mind producing thirty-eight hideous stories just to arrive at the one. He didn’t agonize over every word he wrote: words didn’t enslave him the way they demean me. It’s not all to his credit; words have meaning, and Shon didn’t always take that seriously, if at all. It’s why he could be completely wrong, hateful, hurtful, vulnerable, exposed, sordid, stuck, or even trapped. He sometimes was caught off guard by how much his words gave him away because he didn’t seize the meaning before he let them go.

He had to apologize a lot. But he always did; he always knew how. It came so easily to him that it made me think it was possible to apologize at any moment that an apology proved necessary. I always sort of thought apologies were like money: valuable, secretive, improper to talk about in public, tucked away in savings and stored away for the future, always the future. Used improperly, an apology would be openly vaunted, thrown around needlessly, carelessly, used always for the present moment to satisfy momentary desires–that’s how often Shon apologized to me. He always meant them. They were scrupulously sincere. I hated that he never gave me a chance to be unforgiving.

He allowed himself the freedom to write the same way he banged on the piano. He could smash words together, pile them up just to topple them over, color them with paint or splash them in mud, even smear them in his own blood if he needed them to cry out in agony. Shon enslaved words and tortured them into generational submission. Almost every single thing he sent me I couldn’t read or didn’t know how to read and would stop trying because it hurt my head and sometimes my feet, but when he, or the words, or both, were finally ready, he’d send me a masterpiece that would smother me in illustrations so vivid, story lines so thick, characters so alive and miraculous that I’d either drown in self-loathing for my utter incapability to write the way he could or I’d fly above hope, above talent, above reason with a soaring belief that I can write, too, simply by gripping Shon’s authority.

His work, whether luminous or despairing, inflicted a grotesque burning of the emotions, searing the flesh. And so was his presence, which is why I almost always struggled to be around him even while relishing his asymmetry.

Shon was apprehensive. Not of the bad, but of the good. If he were here in the void of 2020, vindication would be his. It was the joy, the present, the everlasting-ness of love that he didn’t fight for and wouldn’t take the time to see, to understand that the good wasn’t settled in goodness, but in the trying.

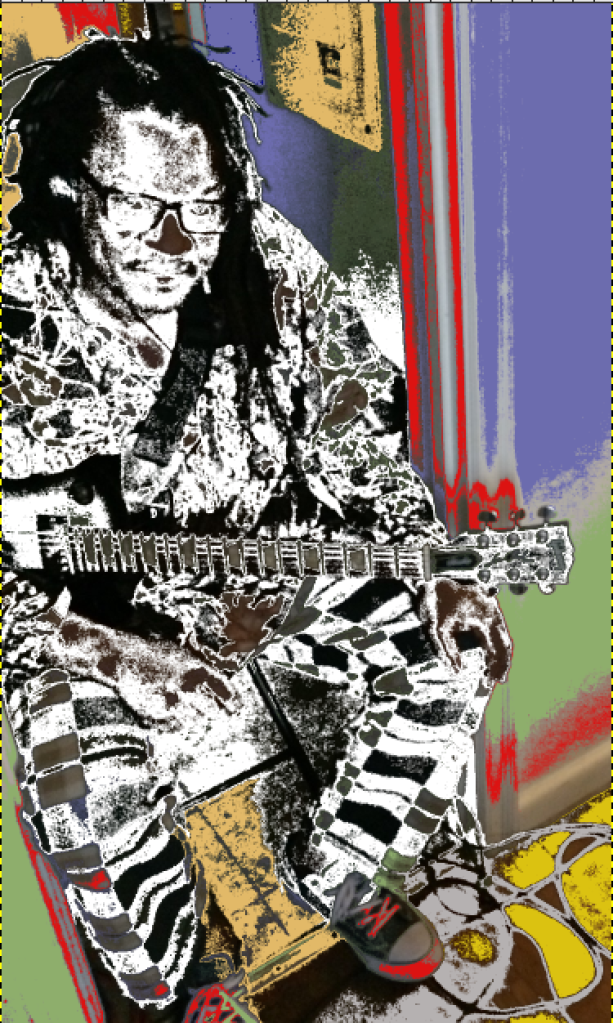

The trying part of his life was playing his creature; his guitar. Shon, the most miserably enthusiastic person I oftentimes wished I’d never grown so close to, had an improvising mind that metamorphosed his guitar, splitting the seven strings he had on that creature he called a guitar into two dozen more. It grew legs every time he touched it. Sometimes it breathed fire.

It was the only trying part of his life that could have kept him alive if he just played it without thinking he ever needed anybody else to do it. All those musicians who were never worthy of him helped kill Shon, too. He never should have started needing them.

And that’s how he always talked to me. Like he needed me, like he couldn’t create without me. It was never true, but he made it true. He forced it into truthfulness.

I write the forced truth now because Shon would hate me all the way down deep in the pitch darkness and rotting flesh of his grave if I didn’t. He wrote his own eulogy and told me to read it at his funeral. The last sentences of the eulogy: “He is not resting in peace because that would be a huge tragedy; so don’t wish him a peaceful rest. That pisses him off.”

Since Shon already wrote his own closing, I don’t need to close for him:

“He is not gone, he has just gone further, and that takes balls…He chose the loneliest path because he followed his heart, perhaps into immanent doom, but knowingly. When the final day came there was no sense of human understanding. He knew it. It challenged him through vivid imagination and plagued him all of his life….So he decided to die. Yesterday never ended for him. There always was that sort of contrast of now against memory and that is what took away his tomorrow. Yes, we cannot, and will not live in the past, but there are dreams of a war that could’ve been fought a little harder. Instead of sleeping with defeat, struggling with the now, and all of time, he decided to belong to nothing.”